The Energizing Rush of Positive Anger

A Conversation with Nick Brandt

By Pamela Chen

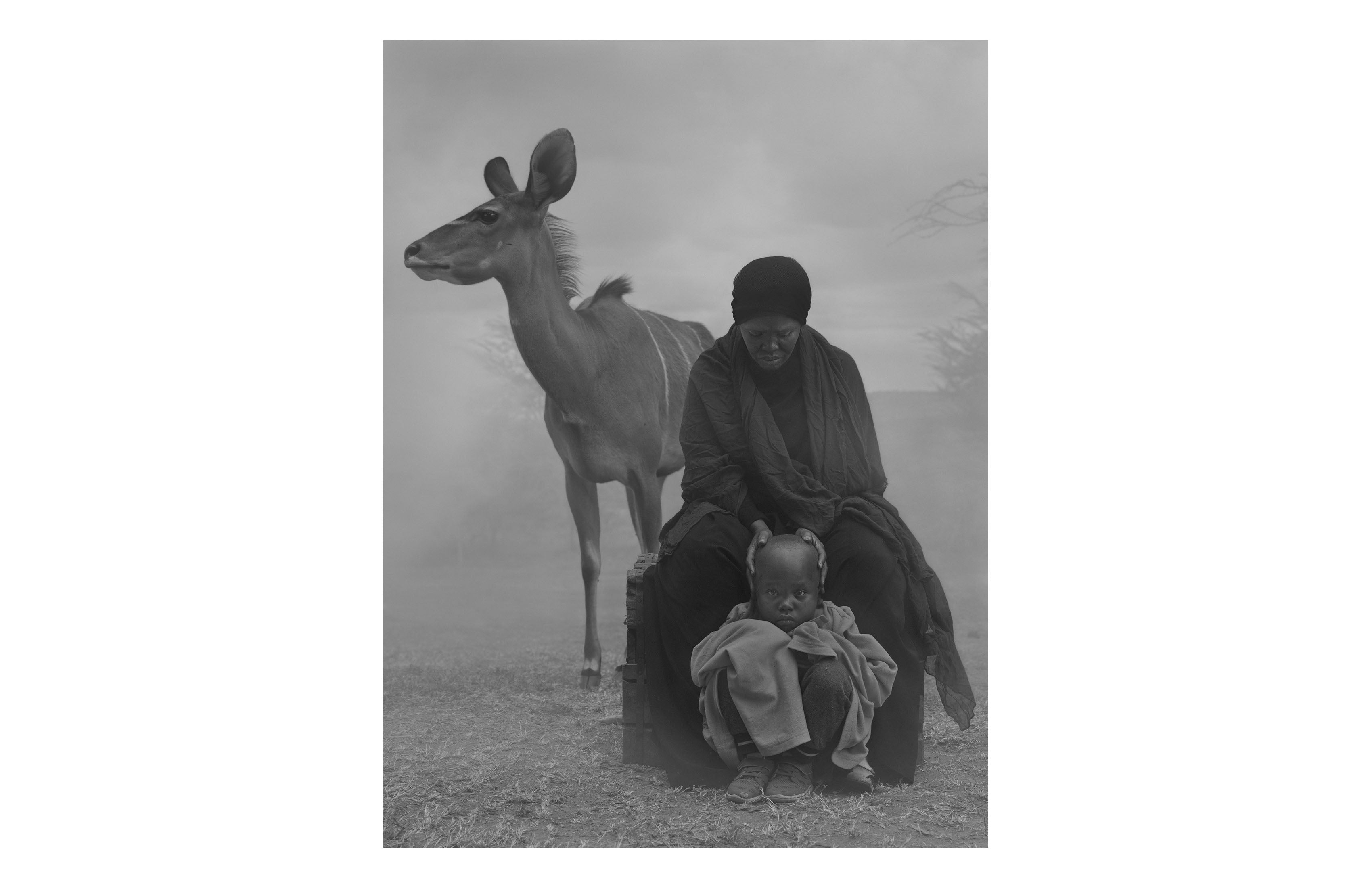

Nick’s lifelong clarity of conviction is his not-so-secret weapon. It powers the vision behind his latest work, The Day May Break, in which human and animal survivors of climate change stand together, shrouded in a barren and foggy post-apocalyptic world. He’s created a somber tableau, but Nick has also captured something eerily comforting in the quiet togetherness of the survivors. This visual tension reveals his true purpose: he is here on behalf of the survivors, and demands your anger and attention to make a change.

What is that change? Channel that anger into doing something to help, says Nick, it doesn’t matter what it is. Stop buying plastic, clean up a beach, save a homeless cat. Being angry enough to act comes with its own energizing rush, and it is this energizing rush of positive anger he hopes to inspire, to help lift us out of perpetual inaction.

As for channeling his own positive anger, he co-founded Big Life Foundation in 2010, which has become a thriving, effective organization that partners with local communities to protect 1.6 million acres of wilderness in East Africa today.

In our conversation, Nick shares reflections on why this work suits him so well, his outlook on how to make a positive impact, and the power and limitations of photography as his medium of choice to do it.

Pamela: OK, here we go. Hello, Nick.

Nick: Hello, and Hattie.

Pamela: Yes, and Hattie,

Nick: OK, so I've got Hattie up here with me for now, just in case I'm really boring. That way, everybody can look at her instead of me.

Pamela: Well, hello, Hattie. Thanks for being here as well.

Nick, you have been so productive this pandemic. You've created an entire new body of work and published The Day May Break. You really have sharpened your focus around climate change. Not only that, but also your personal evolution as an artist.

Nick: Yes. I wonder if it's possible to be serious about anything with a large dog head between you and I.

Pamela: Hattie has such a serious face.

Nick: I know. She keeps me amused if nothing else. I guess I should probably tell her to get down so we can go, because I'll just keep cracking up. Hattie down, Hattie down, and then I'll get to the question. Go on. Good girl. Yes.

Well, first of all, I kind of maintained my sanity through the initial COVID period conceiving this project and then going off and shooting it. In that respect, I actually have had a good Covid War. Climate change. This is something that I have been watching with growing horror for the last 30 years. I mean, how could you not be as long as you've been alive that long and sort of reasonably sentient? But I was busy dealing with other planetary crises like biodiversity destruction, and the death and destruction of the natural world, and other such, you know, trivial matters.

But climate change obviously continues to become more and more the single most consequential issue facing humankind. I felt quite belatedly that I absolutely had to switch to addressing that.

Pamela: How does it compare when you look at the work that you were doing before this project? How do you see it as the next chapter?

Nick: How to see it as the next chapter? It's inevitable because it is the most consequential issue facing us. I can't put it any other way than I feel compelled to have to address it. I guess an important point then is, if you look at the new work, this is the first time that people have become the literal focus of the photographs. With climate change that most directly impacts humans, as well as the animal world. Thus bringing people into the work into the foreground for the first time.

Pamela: Yes. I think there's something so striking and magical when you see the pictures because the people are so integrated. I don't really even know the right word. It's so intimate to see them so close and interacting with the animals in such a quiet way.

Nick: I hope so. It was absolutely critical to me that everybody be photographed together in the same frame at the same time. Of course, in this day and age, everybody thinks it's Photoshop. It would never have been as good if it was Photoshop. There was a wonderful integrity to having the people, who were very calm, very patient, very gracious, right next to animals who they were not remotely fearful of, because the animals had such a good relationship with their carers.

To be clear, all the animals in the photographs are rescued animals who could never be re-released back into the wild. They spent their lives used to the company of strangers. That all went incredibly smoothly, and it created the possibility of those quiet moments that you describe.

What I should embrace and accept is that those of us who think similarly each find a kind of strength, and solace, and extra gained motivation by knowing we're not alone.

Pamela: About the people, they are in these quiet moments interacting with the animals. These are wild animals that seem so distant for most people. You also included stories about their lives and how they were impacted by climate change.

Nick: Yes. This is an interesting challenge that I think is an interesting topic for any photographer dealing with anything based in real life, documentative, sociopolitical, environmental. How much can we rely on just purely the image to tell the story? I wish that these photographs could tell the whole story just through imagery. I can't do it. I don't know how to. I can't figure it out, because when you read the stories and you find out how the people in the photographs have been so heavily impacted by climate change, what happened to them and where they are now. Also, indeed, the animals: what happened to them and where they are now?

That gives so much extra depth, so many more layers to the photograph. An understanding and empathy for the view for those people. It's a struggle, you know. I always want people to read the accompanying text, but in this day and age, people read even less and less. There's even more attention deficit and overwhelming amount of visual imagery. It's just harder and harder to expect people to actually engage with the stories behind the images. I'm sure this is something that a thousand and one photographers deal with.

Pamela: Now we're talking about this idea of art and how it can affect change, which is something that you've been living for the last 30 years. It’s like the picture has become just a starting point for you.

Nick: This is another challenging notion for me, because on the one hand, I create purely for myself. I take photographs purely to please myself. I never, ever, second guess how the viewer might respond when I'm in the process of taking the photographs. Obviously, you also cannot help but want people to be moved and affected by the work. So, when you get to the selection stage, you might find yourself thinking, ‘is that going to move people?’

If I think through all the photographs from The Day My Break, is there anything that I put in that I didn't like, but I thought would have an impact? No, not at all. That's not something I would ever do. But, of course, you want people to be affected.

The act of positive anger, the act of active anger, is energizing. It's energizing. It's almost like it can be a bit of a rush.

There's still the issue, which you and I spoke about in a previous conversation, about the concern about preaching to the converted. I always worry that I am mainly preaching to the converted, the people who think similarly to me. Therefore, how much change can I affect? Having never once in my life successfully persuaded a climate change denier to believe in climate change, maybe that's a lost cause. What I should embrace and accept is that those of us who think similarly each find a kind of strength, and solace, and extra gained motivation by knowing we're not alone.

It galvanizes people who might be uncertain, despairing, to just go, ‘you know what, screw this, I need to do something as well.’ When I think of it in that way, what I'm doing is not so frustratingly, potentially futile as I sometimes fear it might be.

Pamela: Well, you talk a lot about this idea of active anger, as opposed to passive anger. I love that concept.

Nick: Yes. That's easy because when you are despairing and you don't know where to begin, you don't know what to do, you just sink. All of us sink into a sort of apathetic depression and sometimes a bitterness and a negative anger. Then you need to get up and galvanize yourself to do something about it. And it doesn't matter what it is. It can be going to the beach and clearing all the plastic garbage off the beach. It can be saving a homeless cat. I keep coming back to plastic, but I'm kind of obsessed with it.

I can't bring myself to go to the store and buy any one-use plastic. I find it upsetting. Especially in America because we increasingly know just how little of the stuff we put into recycling genuinely ends up getting recycled. The best thing you can just do is just not buy plastic.

The act of positive anger, the act of active anger, is energizing. It's energizing. It's almost like it can be a bit of a rush. There's a retail rush, there's a philanthropic rush. As you know, I started a foundation, and I've become very aware of donors getting a philanthropy rush. A feel good factor of donating and feeling like, ‘I've made a difference. I've helped.’ I think there's also the rush of positive anger.

Pamela: I sense it coming through in a lot of your writing as well. You speak very passionately about your subjects and your work, but also this time we're living in, which you describe as climate breakdown, climate chaos.

Nick: Yes. That's not my phrase. I believe that it was George Monbiot, in The Guardian, first used climate breakdown and then moved on to climate chaos. Any of those apply. Obviously, climate change is way too anodyne a phrase considering the apocalyptic situation across the planet currently.

The point being that both human and animal are all living on the very same small planet... We are connected in our suffering from the destruction of the natural world.

Pamela: Can you tell me a little bit about how this work has been received, these stories?

Nick: That's not really for me to judge. I try to avoid going online and reading anything because I get pretty tense. The equivalent of not reading your own reviews, I find it much more mentally healthy to just plow on, get on with it. You get on with your work and just hope that it's getting a good response.

Pamela: What is it that you hope people do see? Like what would a good response look like?

Nick: What would I hope that they would see? I would hope they would look at the photographs and see that there are both humans and animals within the same frame and understand why. Why have I put humans and animals within the same frame, in the same space, but never looking at each other? I would hope that they would somehow comprehend why. There is a phrase I really hate that was used about COVID a lot at the beginning, which is we're all in it together. Of course we're not, there's a complete inequality. People who are poor, people who don't have access to medicine, suffer much more than privileged wealthy people.

The point being that both human and animal are all living on the very same small planet. The resources are incredibly finite. Both human and animal will suffer the similar consequences. Animals will die and humans will suffer, and a lot of humans will die, just not to the same number as animals. We are connected in our suffering from the destruction of the natural world.

I discovered that photography for me was the medium through which I could best express those concerns, those passions, those obsessions.

Then I would hope that the series progresses. For example, right now, you and I are talking on January 12th, 2022 and all being well, COVID permitting, in three and a half weeks, I'm off to Bolivia to begin stage two of The Day May Break. I would hope as I progress to various countries, money permitting, that people see that they have empathy again for people who are really suffering. People are suffering from the effects of climate change.

So far in Kenya and Zimbabwe and Bolivia, those people, you already know this, there's a lot of people watching this that already know this, that those people have suffered the negative consequences of climate change as a result of the massive disproportionate amount of carbon emissions from countries like the US, the UK, Australia, et cetera, et cetera. They did not expect their lives to be screwed because of the greed, indifference, and apathy of rich Western countries.

Pamela: I was very moved when I looked at the work and I read the stories. Why photography? Why is photography the medium? Do you think that can do this?

Nick: Well, that's just for me. Everybody's got their own different skill set. I originally was a director for far too many years. Trying to express my concern about the environment and my love of animals in the natural world through the medium of film, but wanted to do it through a fictional format, not documentary. I was getting incredibly frustrated and watching my life fizzle away.

I did not imagine myself as starting an organization of my own. My wife warned me that it would completely take over my life and I refused to believe that. As usual, she was right.

Then I discovered that photography for me was the medium through which I could best express those concerns, those passions, those obsessions. The beauty of photography, if you don't go crazy like I did on my previous project, is that you can create how you want, what you want, what you want. Unlike film where you're always waiting for somebody to give you money. It's intensely frustrating and you often waste the most energetic years of your life waiting for somebody to give you money to create.

The beauty and glory of photography is, you just go do it, within reason. That is the democracy of photography, the democratization of digital. Once you've got the camera, it doesn't cost anything. Then it's distribution. Then, how do you make a living from it? Of course, in this 21st century world, where people read less and less, it becomes even more of a potent art form. It's a good creative art form in which to express yourself.

Pamela: You also have expressed yourself in other ways, like the founding of Big Life Foundation, for example.

Nick: In the years that I was first going to Kenya and Tanzania, I was always curious about what organization, what nonprofit can I donate to to help. The safari guides and other people I would talk to were pretty negative. What you really want is local organizations on the ground because, to generalize, they tend to be the most effective and impactful.

Around 2010, when I went to Amboseli (National Park), where all the photographs of elephants that I had taken prior to that, I saw this dramatic escalation in poaching. It was outside the national park, which was tiny. The Kenya Wildlife Service didn't have the resources to make much of a difference because they were just contained within this 100,000 acre park. Outside of the park, where 80 percent of the time animals roam, there were no non-profits who had any kind of sufficient funding to make any kind of meaningful difference. There was almost nobody there with any kind of sufficient money.

So I felt I had no choice but to, completely by surprise. I did not imagine myself as starting an organization of my own. My wife warned me that it would completely take over my life and I refused to believe that. As usual, she was right.

Because I had access to wealthy collectors of my photographs, my very first meeting was with a collector in New York, who I went to see and I told her what I wanted to do. I made her cry, and she donated $1 million in support. With that million dollars, me and my co-founder, Richard Bonham, who is this amazing conservationist who lived in an adjoining area within the Amboseli ecosystem, he was able to hire rangers, buy Land Cruisers, build outposts, get tracker dogs. The whole thing.

The key to it all, the sort of holistic ethos of Big Life, is that if conservation supports the community, then the community will support conservation.

Within a matter of months, some of the worst poachers, who had been operating with impunity for decades, were being arrested. What we did, something that nobody had done before, was we established ranger outposts on the Tanzanian side as well as the Kenyan side. As poachers came over the border between Tanzania and Kenya to kill elephants, and then escape back over to Tanzania with ivory, the Kenyan teams would report to the Tanzanian team. Then the poachers would be arrested on the Tanzanian side. In pretty short order, a lot of the worst poaching was taken care of.

Now you cut to 11 years later, there's almost no poaching of any animals in this entire area. Big Life now has over 300 rangers, protecting 1.6 million acres of ecosystem with something like 36 outposts, multiple patrol vehicles, aerial monitoring, tracker dogs, night vision, surveillance, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. That, amongst many other things that I won't get into now, has resulted in a surprisingly great success.

The key to it all, the sort of holistic ethos of Big Life, is that if conservation supports the community, then the community will support conservation. Almost everybody within Big Life is locally employed. The fact that there are wildlife scholarships. The fact that there is compensation for livestock killed by local predators. The fact that we have built 100 kilometers of fence to protect farmers' crops from being trampled by elephants. All of that has resulted in local communities that are very supportive of the conservation efforts. That is really the only way forward in increasingly populated areas in Africa in the 21st century.

Pamela: That's incredible. The work that you've created as a photographer has opened up all of these other avenues for change where you've directly walked the walk. I'm very curious: what drives you? Were you always like this? What was the beginning of this journey for you?

Nick: Yeah, I was always like this. I've always been like this. I came out apparently, it seems, fully formed with this initial intense love for animals and the natural world. At the youngest of ages I would just run off to the park that was very close to where I lived in the center of London. That was my sanctuary. The only thing that I liked about childhood was escaping there to bird watch and study the plants and the trees and the flowers.

I don't even know how I survived as long as I did in the city. I really don't like urban environments at all. And I'm drawn to anything that involves injustice. I consider it a monumental injustice to billions of lives that the planet is being destroyed by human greed. If there wasn't that, I would be drawn to some other kind of injustice.

Pamela: We talk a lot here about the work and what the work has led to in your life. Why does this life suit you so well?

Nick: Well, first of all, I need to be creative. I don't have a choice. It's a compulsion, as I'm sure most creative people would say. I found it fascinating that prior to starting the work on The Day Will Break, the combination of COVID and Trump was resulting in every single night of intense, jaw clenching nightmares, headaches.

I'm drawn to anything that involves injustice. I consider it a monumental injustice to billions of lives that the planet is being destroyed by human greed.

Literally, the day that I started photographing on The Day May Break, it all vanished because my mind was engaged and alive with the possibility of what I could achieve creatively. So, there is that. And then there is the need to always feel like, I'm going to say this utterly cliched phrase, but that you can make a difference. It's such a cliche. I wish I could come up with a better...I wish there was another way of saying that.

Pamela: Well, why do you think it's a cliche?

Nick: Because it is, but it's true. I mean, cliches are often true. I just don't want to speak in cliche if I can help it. It's galvanizing, it's energizing, if you can do something. God forbid, if I were to get cancer, the first thing I know that I would be doing is trying to figure out what are the things that I can do to live as long as I can to cure myself. Without just thinking, I'm just going to do it with a bunch of supplements. You can get into a whole psychological discussion of, 'well, what is it that you need, you can't function, without that need to act.’ But I do. I can tell you, I am not good when I don't have the possibility of action. I would just dive into a very dark place if there was absolutely no potential of hope.

People would look at the photographs and say, well, where's the hope? They say, ‘oh, you know, you're such a pessimist!’ No, I'm not a pessimist. I'm a realist. You just have to look at the statistics. I'm just following the science. I'm just following the inevitable progression of the current path that humanity is taking. I'm following the science. I still do what I do, because I believe we should be doing everything we can to mitigate the damage. We already know there's going to be loads of damage, but what use is it just to sit back and let it just go to shit? Let's do everything we can to mitigate the damage.

Pamela: In a past conversation, you and I have talked about how pictures can do that. The pictures that you've made are so surreal and beautiful, in a classic way, and in this kind of pensive, modern way. You talk about how you respect photographers who can photograph what's harder to look at.

Nick: In terms of what you're referencing, I am in awe of photographers who can go into really, seriously uncomfortable places that are intensely distressing, such as slaughterhouses and abattoirs. Where they are photographing animals whose lives can never be saved. I couldn't do that. I would become intensely depressed. I would become angry to the point that I would end up committing violence and being arrested. I am in awe of those photographers who could do that and walk away and still not have PTSD, or maybe they do. Now, I've forgotten what part of your question was. I just wanted to reference what you were referencing.

I still do what I do, because I believe we should be doing everything we can to mitigate the damage. We already know there's going to be loads of damage, but what use is it just to sit back and let it just go to shit?

Pamela: But the role that your photography plays is different.

Nick: Yes, because I can't do what they do. Let's just go back to The Day May Break, which is what started this conversation off, the most recent work, and it's the work I'm going to be working on for the next X number of years in theory, as long as the money lasts.

Everybody in those photographs, both human and animal, are survivors. Even if people will look at those photographs and think, ‘oh, blimey, it's all a bit bleak’. No, they've all survived. They're all alive. Those animals were rescued and then those people survived the trauma and hardships imposed on them by climate change. They didn't drown in the river, even if their kids, God help them may have. They made it out of losing their farms, losing their livestock. Even though they were maybe forced to the city to do just menial labor, they still are alive. They survive.

I think I should just mention to that point, the photographs, the sales, the proceeds from the print sales or a share does go to those people in the photographs. They've already received an initial royalty payment. It's not like, photograph prints of Richard sell so Richard is to get the proceeds, it doesn't work like that. That wouldn't be fair. Everybody gets the same amount, regardless of whether the photograph of them sells or not.

But also, what's really incredibly cool that's now happened twice, is a collector of a specific photograph, in one case in Kenya, another case in Zimbabwe, they have donated, in one case, three thousand dollars, in another case $3500. That is enough to really transform lives, like with the case of Sofia, this little girl in Kenya. That's going to pay for her school education. That is amazing to me. That I find really gorgeous. That one print sale. One print sale to one collector can help transform somebody's life who got screwed over by climate change from another country.

Pamela: Wow. And you say you're going to keep doing this work until you run out of money?

Nick: Yeah, It's not as easy as I thought. I didn't think it was ever going to be easy. I always knew it's going to be hard. But A, it costs a lot of money because these are productions which have a number of people. We're bringing people who are being impacted by climate change from all across the country. Right now as we talk, there are four researchers out in various parts of Bolivia looking for people with those stories. I'm getting sent photographs every day and then I'm casting. It's not really casting, but I'm choosing the people’s stories. Then they'll come and they'll get paid to be there for a week or so while I photograph.

Everybody in those photographs, both human and animal, are survivors. Even if people will look at those photographs and think, ‘oh, blimey, it's all a bit bleak’. No, they've all survived.

I'm actually finding it quite hard to get enough, like, for example, I had originally planned this series to start in California. Then COVID happened. With all the restrictions in that first year in 2020 it became too logistically impractical to be able to photograph in California. That's why I then started in Kenya and Zimbabwe because I could get into those countries.

Since then, I've tried again in California. So far, nobody's interested. Sanctuaries aren't interested. It's like, wow, OK. You're getting exposure with the work. I'm paying you. I'm giving daily shoot fees that are not inconsiderable, to help you fund your sanctuary. You're going to get exposure. And I can't get people who are interested so far. Which is a shame. It could mean ultimately, hey, I don't do California. The American West is going up in flames. Where I live went up in flames. I'm worried there are going to be these gaping holes in what should be a truly global series.

Having said that, also, I can only go places where there are rescued animals that cannot be re-released back into the wild. They cannot just be animals that were bred with no back story because then they're just props. Then there's no story. There's no emotion. The photograph might look the same, but the story behind it, which we were talking about, wouldn't be there. I'm sorry, I need that story. I want every story behind every photograph to have an integrity and a depth to it that is not bullshit. That is not just some animal that's basically a stand in prop for, oh, and here's a fill in the blank. That happens to have been bred with not even its parents having been originally rescued. So, it's proving quite complicated with the number of places that I can go.

Pamela: I had no idea that there was the casting of the animals as well. Was that part of the initial idea?

Nick: Oh yes, totally. For example, also with COVID, there's no animal I want to be in the company of in the world more–well, actually, there's an animal that I want to be in the company of, that I've already been with, manta rays. My idea of heaven, those flashes of memory in your dying moments, one of them for me, will be diving with manta rays.

But of animals that I've never been in close proximity to: orangutans. I know that now with COVID, we will never again be able to be in close proximity without masks. I can't put my human subjects maskless, close to any primate. By which I mean, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, et cetera, et cetera. Even though we're going to great lengths to be careful. I'm always very superstitious about talking about projects before they've happened. For example, with Bolivia, we're making sure that everybody, all the people coming to shoot, are all vaccinated. It's sort of being as careful as we can to be responsible.

One print sale to one collector can help transform somebody's life who got screwed over by climate change from another country.

Pamela: Which actually brings us full circle. This is a project that was born in the pandemic. Do you foresee working on this beyond the pandemic?

Nick: Oh yes, it's going to. Well who knows what that means?

Pamela: Yes, I know. As soon as I said that I thought, what am I saying?

Nick: Yes. What does that mean? The pandemic eventually becomes endemic. We don't know exactly when that will be, or if it'll just vacillate between pandemic and endemic. We've no idea. Again, this comes back to until the money runs out, which I think it will.

And, until there are no longer places I can find where I have the ability to photograph. I think back over interviews that I've done over the years. There are all these times that I've said, Well, this is what I do. I would only ever do, fill in the blank. Then four years later, it's complete garbage, what I said.

Pamela: The first thing you said to me was, I don't want to talk about anything in my past because what I'm doing now is what I'm doing now.

Nick: Right? Yeah. Even things like the most obvious one being, I will only ever shoot film. I will only ever photograph in black and white. Well, both of those went out the window when the aesthetic and emotional and practical situation arose. When black and white and film are no longer an option for any of those three things. I keep putting my foot in it with these kind of very absolute statements. I have to learn not to do that.

Pamela: What is really revealing is that you're not driven by the medium, so much as you are by the messages you're trying to convey behind them.

Nick: Except that I do want to do it through photography. I've had people offer film work. Even film that relates to my subject matter that I'm so obsessed with and live for.

Pamela:You mean film, not film versus digital film?

Nick: No, I'm sorry. I'm talking about directing.

Pamela: Yes, OK.

Nick: I've been offered directing stuff and I have turned it all down. Up until now because I'm on this obsessive photographic path of photographic expression. I don't want to waste a minute doing film. I'm very frustrated that it took me so long in my life to reach the point of comprehending that photography was the best medium for me. It took until I was thirty-seven.

Pamela: Why is photography the form, and why were you so frustrated?

Nick: I was frustrated because I went down a path where I was relying on other people to give me the money to create, rather than just going off and doing it. Which with photography, you can.

I can only go places where there are rescued animals that cannot be re-released back into the wild. They cannot just be animals that were bred with no back story because then they're just props. Then there's no story.

Pamela: But surely, The Day May Break is not a cheap shoot.

Nick: No. Then go back to the previous one, This Empty World. That's why the essay in The Day May Break is called the acoustic album. After the insanely elaborate, epic scale of This Empty World, The Day May Break is like the unplugged project. The acoustic version. I forgot what the question was again.

Pamela: You said that you were frustrated it took you so long to find photography.

Nick: Yeah. I wish I had been a photographer from day one. Not spent years and years miserable trying to do it right. I'm also not good at having clients. I need to just do my own thing. I love the collaboration with the crew, when we're all working together. We don't have some money person telling us what to do. That didn't suit my temperament well.

Pamela: Also, the output is quite different. You have the single frame and the story.

I read what you wrote about how you choose the frame. You shot it in digital so that you could look and know that you have it before you can move on.

Nick: That was to do with the fog. The only reason we used digital in The Day May Break was the fog is constantly drifting through. Every single frame is different because there's always some breeze. The fog is such a fundamental part of the aesthetic because it creates a symbol of the natural world that we know is disappearing before our eyes. Of course, every single frame is revealing a different part of the background. The way it interacts with humans and animals. You can't remember in that split-second moment how it looked. At the end of each session, I would always go through and see what worked.

I'm on this obsessive photographic path of photographic expression.

I don't like looking at the image during the shoot. I like being in the moment, connected to my subjects. If I start looking at that screen, which I never do, I never look at that screen. I don't even know how it works, basically. That takes me out of the moment.

Pamela: The final image. Do you know you have it, when you have it?

Nick: No. Yes. No. Yes. No, I don't know. The crew will say, ‘are you happy with what you got?’ at the end of a session. I've got absolutely no idea. There are stages. Stage number one is you load it onto the computer. You go, ‘maybe’. Stage number two is the editing process. Stage number three is looking at the prints.

I cannot tell whether I have taken a good photograph until I look at the print. Everything, to some degree, looks good backlit on a computer screen. Actually, that's not true, I take that back. My previous work, its crap on a computer screen, This Empty World. It only looks good when you see the prints because they're huge and they have a very different quality to viewed on computer.

I can only tell whether I've taken a good photograph, in my opinion, when I see the physical print. Then I'm still not happy because now I have to see what I feel about it in a year. Still, I'm not happy, because it takes about 10 years to figure out whether you're happy with it. I'll tell you whether I'm happy with a photograph after 10 years.

Pamela: Well, we'll have to check back in then. We're reaching a pause point here. Is there anything that you feel like we haven't covered that you'd like to cover today? We've talked a lot about your journey, the very moving work of The Day May Break, and what drives you.

Nick: The only thing that I would say is for anybody watching this please, where possible go look at the prints in an exhibition. That's how the work is meant to be seen. It's not meant to be seen on your phone. Failing that, buy a book. The books are large, beautifully printed. Failing that, on your computer, go to my website and look at the photographs with the zoom bar. Whatever you do, please don't look at them on your phone.

Pamela: Well, that's a good closing thought. Is there anything that you'd like to add for Vital Impacts?

Nick: First of all, the first iteration of Vital Impacts, which ends on January the 17th, 2022, has been wonderful because Ami, in her extraordinary generosity, made Big Life one of the four recipients of the proceeds. That was amazing. I was not expecting that. I have to thank her. Not just for that, but obviously for the extraordinary amount of work that has gone in between her and Eileen for putting it together. It's a lot of very, very, very tedious behind the scenes admin that has been involved and organized, with shipping prints and talking to potential buyers, and being a nonprofit and a gallery and a bunch of other things all rolled into one.

I can only tell whether I've taken a good photograph, in my opinion, when I see the physical print. Then I'm still not happy because now I have to see what I feel about it in a year. Still, I'm not happy, because it takes about 10 years to figure out whether you're happy with it. I'll tell you whether I'm happy with a photograph after 10 years.

The bigger picture is, what a great way for people to donate to great causes and get something back at the same time. And, the photographers benefit as well. It gives them a chance to use that money to do the next project. So, it's a win-win, for the buyer, the photographer, and the organization receiving the donations. With all that in mind, anybody who's got a bit of spare cash and wants a bit of art on their walls, go buy now. There you go.

Pamela: All right. Thank you, Nick.

Nick: Thank you. Yes. Thank you very much indeed for taking the time to do these talks. If you are to go through a lot of photographers, it is a fair bit of research and time out of your busy days.

Pamela: Well, it's been a pleasure to talk to you. I think we can all learn a lot from the passion and dedication that you have and you continue to have for the environment and for photography.

Nick: Thank you. I hope so, thank you very much.